In our cross-border cooperation we report from France, Germany and Greece.

Calais – largest slum in Europe

Police violence against migrants is not new to 2020. It was first highly publicized in Calais. This city in the North of France is a compulsory transit zone for people leaving for Great Britain. Calais became the largest „slum in Europe“ in 2016, before falling off the map in recent years. The subject returned to the forefront of the scene at the end of November, in the heart of Paris. Some 300 exiled people had set up their tents in the symbolic Place de la République after the evacuation of the Saint-Denis camp a few days earlier. A few hours after their installation they were vioently driven out. Beatings, tear gassing, humiliation and manhunts lasted late into the night. Journalists were also violently attacked.

A cycle of violence

As of 2015, non-profits are mobilizing to highlight the violent treatment of exiled people following the example of Calais Migrant Solidarity. They put a video online showing the violent behavior of CRS (Republican Security Companies, editor’s note) towards migrants in May of the same year. They were trying to get into trucks on the ring road leading to the port of Calais to take the ferry to England. The IGPN (Inspectorate General of the National Police, editor’s note) was seized. In December 2018, a report by four associations (Utopia 56, the Migrants‘ Hostel, Refugee Info Bus and the Cabane Juridique) counted „244 acts of police violence“ against migrants over the year.

The report also referred to „389 cases of abuse of power by law enforcement officials, 52 of which were accompanied by violence„. Violence – verbal and physical – as well as tracking, are two methods commonly used by the police in recent years, noted the associations.

Strategy of repression

François Gemenne, a researcher specialized in migration governance, considers that violence against migrants has become „a norm insofar as each of these evacuations is turned into a communication operation above all„. And to affirm the words of our colleagues at Infos migrants: the government wishes to „dispel the impression that it is pursuing a lax policy of letting migrants do their own thing„. The strategy of repression, for its part, consists of invisibilizing people, denying their existence by constantly pushing them „out of our cities, out of our borders, out of our fields of vision with the objective of making them invisible„, affirms the researcher, a professor at Sciences Po, in the same interview.

Open letter to the Prefect

As for the people concerned themselves, they have sounded the alarm on several occasions. Notably in an open letter sent on November 16, 2020 to the Prefect of Pas-de-Calais. In it, Eritrean exiled men from Calais denounced the repeated and gratuitous violence they suffered: „The CRS are making our lives a living hell!”. The violence is said to have intensified since the beginning of the second confinement and this group of 150 people who occupy an area named ‚BMX‘ in Calais castigate: „a democratic country cannot be considered as such if it uses physical force in this way.”

Also in Calais, on November 11th, an Eritrean national was seriously injured in the face, following a shot from an LBD40 (40mm defensive ball launcher). Neither the use of this war material, widely criticized by human rights organizations, nor the tear gassing or beatings were commented on by the executive.

…where the cameras do not see

On November 23rd, in Paris, the images of the evacuation of the 300 migrants who had settled in Place de la République shocked and revolted many. It is a new awareness for a large part of the population. However, in the north of France, and particularly in Calais, the associations observed an almost daily brutality. The communication from the Interior Minister and in particular the tweet below show the ambivalence of the State on this subject.

Certaines images de la dispersion du campement illicite de migrants place de la République sont choquantes. Je viens de demander un rapport circonstancié sur la réalité des faits au Préfet de police d’ici demain midi. Je prendrai des décisions dès sa réception.

— Gérald DARMANIN (@GDarmanin) November 23, 2020

Some images of the dispersal of the illegal migrant camp in Place de la République are shocking. I have just requested a detailed report on the reality of the facts from the Prefect of Police by noon tomorrow. I will make decisions as soon as I receive it. (Gérald Darmanin is the French Interior Minister)

Journalists hindered in their work: obstruction and intimidation

On Tuesday, January 5, 2021, two French journalists, Simon Hamy and Louis Witter, had their request for „référé-liberté“ rejected by the administrative court of Lille. Since then The National Union of Journalists (SNJ) referred the case to the Human Rights Defender. Their objective? To denounce the impediment to the freedom of information, which results in the impossibility of covering the evacuations of migrant camps, as access to them is forbidden. At the origin of this procedure were refusals to access the dismantled sites in Grande-Synthe, Calais and Coquelle in five different instances on December 29th and 30th, 2020. Their application to the court was therefore aimed at obtaining authorization to access the sites to carry out their reporting.

"Comment lacérer à coups de couteau une tente de réfugié à neuf heures du matin par trois degrés celsius", mode d'emploi offert par @prefet59 ce matin à Grande-Synthe. pic.twitter.com/HVyHiNAIGR

— Louis Witter (@LouisWitter) December 29, 2020

At the time of the decision, the judge considered that „the claimants had not reported any new evacuation interventions in progress or to come, which they would consider attending, and that it was indicated in the defense by the representatives of the prefectures of the Nord and Pas-de-Calais that the evacuations had been completed„. This was a way of not answering the basic question about the impediment to freedom of information, when on December 29th, Louis Witter had published photos showing security teams lacerating the tents of migrants with knives on the morning of an evacuation on his social media platform.

In a context of authoritarian drift

At the same time, concern is growing in France about the „Global Security“ Law and its infamous Article 24. This foresees one year in prison and a 45,000 euro fine for „disseminating the image of the face or any other element of identification“ of a police officer or gendarme on duty when it aims to „harm their physical or psychological integrity„. The Council of Europe called on the Senate to amend the text, considering that the law „infringes on freedom of expression“ while the United Nations, seized by the League of Human Rights, called on France to review its copy. In the meantime, the French continue to mobilize in a climate of increasingly violent demonstrations. The last mobilization was held on Saturday, January 30th.

Independent media

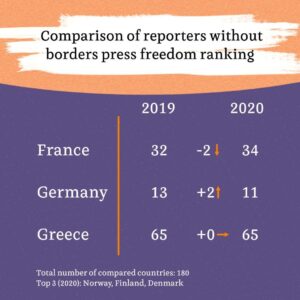

As a reminder, in the 2020 Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, France is ranked 34th (two places lower than in 2019). The NGO notes „a very worrying increase in attacks and pressure against journalists. Many of them have been injured by bullets from LBDs (defensive ball launchers ) or tear gas shots from the police„. Correlatively, French confidence in the media is at its lowest according to the Reuters Institute report: „Trust in news in France is now the lowest (24%) in Europe – hit by coverage of the Yellow Vest protests. Trust in the 24-hour channel BFM has fallen from 5.9 to 4.9 (on a ten-point scale) over the past year and is now the least trusted brand in our list„.

This cross-border collaboration by Guiti News (France), Kohero (Germany) and Solomon (Greece) – three independent medias working on migration – delves into a worrying and escalating trend of police violence during the previous year; not only against people on the move, but against the media professionals documenting their issues as well.

From the infamous ‘jungle’ of Calais to the evacuation of makeshift camps in the center of Paris, and from the “Black lives matter” demonstrations in different German cities to the destruction of the continent’s largest refugee camp, on the Greek island of Lesvos, cases of police oppression across Europe were condemned by press freedom organizations like the Reporters Without Borders.

The other articles can be found here:

- Griechenland – auf Deutsch und auf Englisch

- Frankreich – auf Deutsch und auf Englisch

- Deutschland – auf Englisch und auf Deutsch

Project coordination: Anna Heudorfer

2 Antworten