The German issue is a lack of information on policemen and women’s behavior and their actions towards migrants and people of color. Single cases and individual reports suggest that there is a severe problem. But due to restricted access for journalists and researchers, it is hard to find evidence. For Reporters without Borders this is a threat to press freedom.

No study necessary?

When the US-citizen George Floyd was killed by a policeman, “black lives matter” protests also took place in Germany. They triggered a discussion about police behaviour regarding people of color and about racial profiling. In the course of the debate, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) suggested a scientific study within the police to investigate the current situation regarding racist structures. The national minister for the interior Horst Seehofer (from the party CSU) prevented the conduct of the study because he did not want to see all policemen and -women under general suspicion. He said that racial profiling is forbidden by law and thus does not exist within the police. What is forbidden does not need to be researched, was his argument.

More events fueled the debate: several incidents of right-wing extremism among policemen became public. They spread hate speech against migrants, refugees and muslims in chat groups. Also videos of violent police officers appeared on the internet. A current example for racist police practices is the case of the Black teacher Philip Oprong Spenner. On the 22nd of November 2020 he almost got arrested in his school “Am Heidberg” in Hamburg. He was working late and someone saw him walk through the building. The police arrived with 15 highly armed officers. They did not believe that he was employed at the school – even though he had the keys to the building – but took him for an intruder, presumably due to his skin color.

Als schwarzer Mensch auf St.Pauli zu wohnen ist kein Spaß. Ständig wird man kontrolliert #RacialProfiling. Barakat H. hat genug und klagt gegen die Stadt Hamburg #Polizeiproblem pic.twitter.com/YT3WUNdKkP

— KatharinaSchipkowski (@Kat_Schipkowski) August 12, 2020

Living as a black person in St.Pauli, a trendy neighborhood in Hamburg, is no fun. You are constantly being controlled or searched by the police. Barakat H. has had enough and decided to sue the city of Hamburg because of racial profiling.

Still, minister Seehofer does not see any need for a racism study within the police and called the incidents “individual cases”. Other politicians, especially from the party SPD (social democratic party) stressed the necessity of the study. They were supported by the Head of the Association of German Criminal Police Officers who said that the prevention of the study was wrong because it caused the impression that the police had “something to hide”. Ultimately, Seehofer agreed to conduct a study on everyday police life and practices – a general topic without racism playing a central role anymore.

Lack of evidence on police violence due to restricted access

As a consequence there is a lack of facts and figures. A report by the Federal Agency for Civic Education shows that since the early 1990s there have been studies of racial profiling including collections of single cases and observation studies, surveys on attitudes towards „strangers” among policemen and -women as well as surveys among adolescents with Turkish family history. They all suggest that racism is an issue within the police. But, as the authors of the report conclude, there are large gaps with regard to the manifestation and spread of discriminatory attitudes and practices, which is also due to the difficult access to research and the lack of or inaccessible information base, especially in largely unexplored areas of police work such as investigations, surveillance and interrogations. Anne Renzenbrink, the press officer of Reporters without Borders explains: „Bureaucratic processes slow research in this field down.“ Freedom of information laws are meant to provide journalists access to this kind of data, yet there are still federal states which up to now have no guidelines to standardize these operations. Even in states where regulations have been implemented, miscellaneous exceptions hinder media representatives from successfully obtaining detailed reports. „The issue is that so far there’s no nationwide law ensuring access to information about government offices and authorities like the police“, Renzenbrink elucidates. For Reporters Without Borders „this is a threat of the freedom of press” – hence they urge the government to create more transparency in this area. What we know is that only two percent of the complaints that are filed concerning violent police behaviour go to court, mostly due to lack of evidence. The reason often is a one word against another situation. This number suggests that police officers often cover each other and would not testify against their own colleagues. As a comparison: The total number of all complaints that go to court is 24 percent on average.

Reporting on migration and criticising right-wing actions

In 2020 there has been an extreme increase in the numbers of violence directed at media representatives, especially at demonstrations against Covid restrictions. This violence occurs more often when demonstrations of the right-wing populist spectrum are being covered. In the course of this it is the duty of the police to enable a safe procedure for the media. „Media representatives are meant to report on these demonstrations. It is of public interest – it’s why they should be able to work freely“, Renzenbrink criticizes. Yet reports confirmed by Reporters Without Borders show that in many cases the police not only fails to protect journalists from violent protesters but they also actively obstruct journalistic work. „Although it has improved in recent years, unfortunately again and again some police officers seem to be unaware of the rights of media representatives“, Renzenbrink says. These situations range from not letting reporters pass through barriers, issuing restraining orders during demonstrations to threatening them with custody. As a result a growing number of journalists associations watch these developments with concern as they restrict „journalistic freedom greatly.“ With the aim of improving interactions between police officers and journalists the principles of conduct for media and police from the year 1993 have been updated. Still Reporters Without Borders calls for more action: „There needs to be an emphasis on media law during police training in Germany. Policemen and -women need to know how to treat media representatives in these scenarios“, Renzenbrink highlights. Hitherto journalists associations and police schools have only selectively worked together when reality indicates a „structural deficiency”. Thus nationwide initiatives that educate comprehensively on this matter could initiate progress that preserves the freedom of press throughout Germany. However Renzenbrink emphasizes that education only is not enough: „Authorities have to ensure that these principles are exerted correctly in reality.“

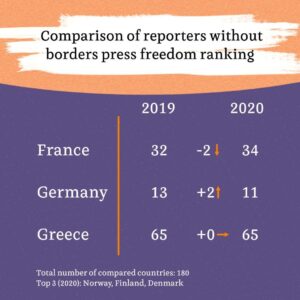

This cross-border collaboration by Guiti News (France), Kohero (Germany) and Solomon (Greece) – three independent medias working on migration – delves into a worrying and escalating trend of police violence during the previous year; not only against people on the move, but against the media professionals documenting their issues as well.

From the infamous ‘jungle’ of Calais to the evacuation of makeshift camps in the center of Paris, and from the “Black lives matter” demonstrations in different German cities to the destruction of the continent’s largest refugee camp, on the Greek island of Lesvos, cases of police oppression across Europe were condemned by press freedom organizations like the Reporters Without Borders.

The other articles can be found here:

- Griechenland – auf Deutsch und auf Englisch

- Frankreich – auf Deutsch und auf Englisch

- Deutschland – auf Englisch und auf Deutsch

Project coordination: Anna Heudorfer

Eine Antwort